Anybody can write a book. Producing a book is very hard. It is right up there with producing a new product for a large company such as General Electric. I have done both and I am not sure which is more difficult.

A new appliance starts with the drawings and specifications. From these you have tools made and you buy equipment that holds the tools. You design the tests and find space for the rest of the production facilities including assembly lines. You make sure pilot models work as they are made on equipment you will use in actual production. And you assure that the boxes they are sold in are made correctly, fit the product and look good.

Authors would be well-served if they had a mental image of the finished product sitting on their shelves. They need a rough idea of the plot, but must be flexible. Characters do not always do what you want them to do. So plot changes will probably occur. A new book requires front and back covers, well-edited text, pictures of acceptable quality, readable type size with the correct font. Covers do sell books, you know. Chapters must be appropriately ended. A book is in fact a list of details that must be accomplished before it can be completed. Tables of contents and indexes must be prepared. There seem to be no end of concerns for you to handle personally before the book is ready for production.

Finally, each author of a new book is an entrepreneur, trying to sell copies in the face of stiff competition from many other authors with the same idea. But if he has a good story, he will never be at rest until he has written it and has seen the book on people’s shelves.

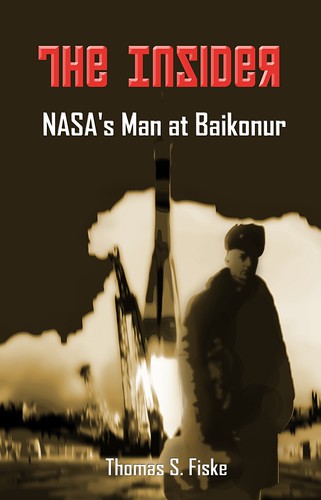

In spite of all this, I have completed my last book. I named it The Insider. It is a novel about an American doctor who spent nine years flying into and out of the USSR during the Space Race when the US and USSR were competing with each other to be the first to land a man on the moon. President John F. Kennedy got Premier Khrushchev of the USSR to allow a NASA doctor to visit the USSR’s secret space launch site about 1963 in spite of problems in Cuba and other US-USSR conflicts. These two world leaders were looking far ahead in the space business.

All the experts say it did not happen. But it did and the man they sent was a friend. The few Government records that still exist support the NASA scientist’s story, even though most were hidden from me and any other writer. It seems that most writer-experts relied on the CIA to tell them the truth, or they relied on people in the USSR to tell them the full story. You may have noticed that books by and about Khrushchev just did not talk about the space program. It seems that the US Congress did not know about the doctor, either. If they did, they would have blabbed about him to everyone they knew. But they thought there was a serious competition and had no idea we were helping the Soviets.

But that was over forty years ago, almost fifty years now. Do you think anybody is willing to release the files on this simple doctor who helped keep Soviet cosmonauts alive? Not in this country. Perhaps one Soviet cosmonaut is still alive who might be interested in telling what he knows.

Anyway, the pain of producing The Insider is almost over. The anticipation of the joy of upsetting self-proclaimed “experts” has kept me to the task. I don’t have any more book ideas now, and this will be my tenth book, so I think I will quit.